Flightseeing the Peaks of Wrangell-St. Elias National Park

By STEVEN YAN

Steven is a talented writer and photographer who flew our “Jewels of the Wrangells Flightsee Tour” this past summer. Enjoy his captivating account and stunning photographs of his two hours in the skies over Wrangell-St. Elias and check out his website for more of his adventures across the globe.

FLY ME TO THE MOON

It's 9:40 AM on the Chitina-McCarthy commuter flight with Wrangell Mountain Air. Kent, our pilot for this flight, descends over Root Glacier as we line up for our final approach. From above, the airstrip barely registers amidst the 13.2 million acres of Wrangell-St. Elias National Park. On the ground, a sparse collection of small buildings dot the gravel clearing. Cessna and DeHavilland aircraft line the runway, poised to spirit today's visitors to and from the wilderness. Kent cuts the engine and silence -- of the quality that's only found through remoteness -- rushes in.

This is my first time flightseeing. Kent imparts some final advice on what camera gear I should expect to use: "Bring it all. You're going to the moon."

My pilot for today's 120 minute flightsee is Ted, who matches then immediately exceeds the profile of how badass I expect my Alaskan pilot to be. Ted flew in from his home in Colorado for the summer. He's climbed and summited Denali -- twice. He's built five of his own planes. We haven't even left the ground and I already have a good feeling about this flight.

LIFTOFF

I immediately appreciate the lack of ceremony that comes with flying in bush planes. Less than five minutes after piling in to the aircraft we're soaring over Root Glacier, with the Stairway Icefall in our rear view. It's the largest icefall in the world outside of the Himalayas -- 7,000 feet of vertical ice.

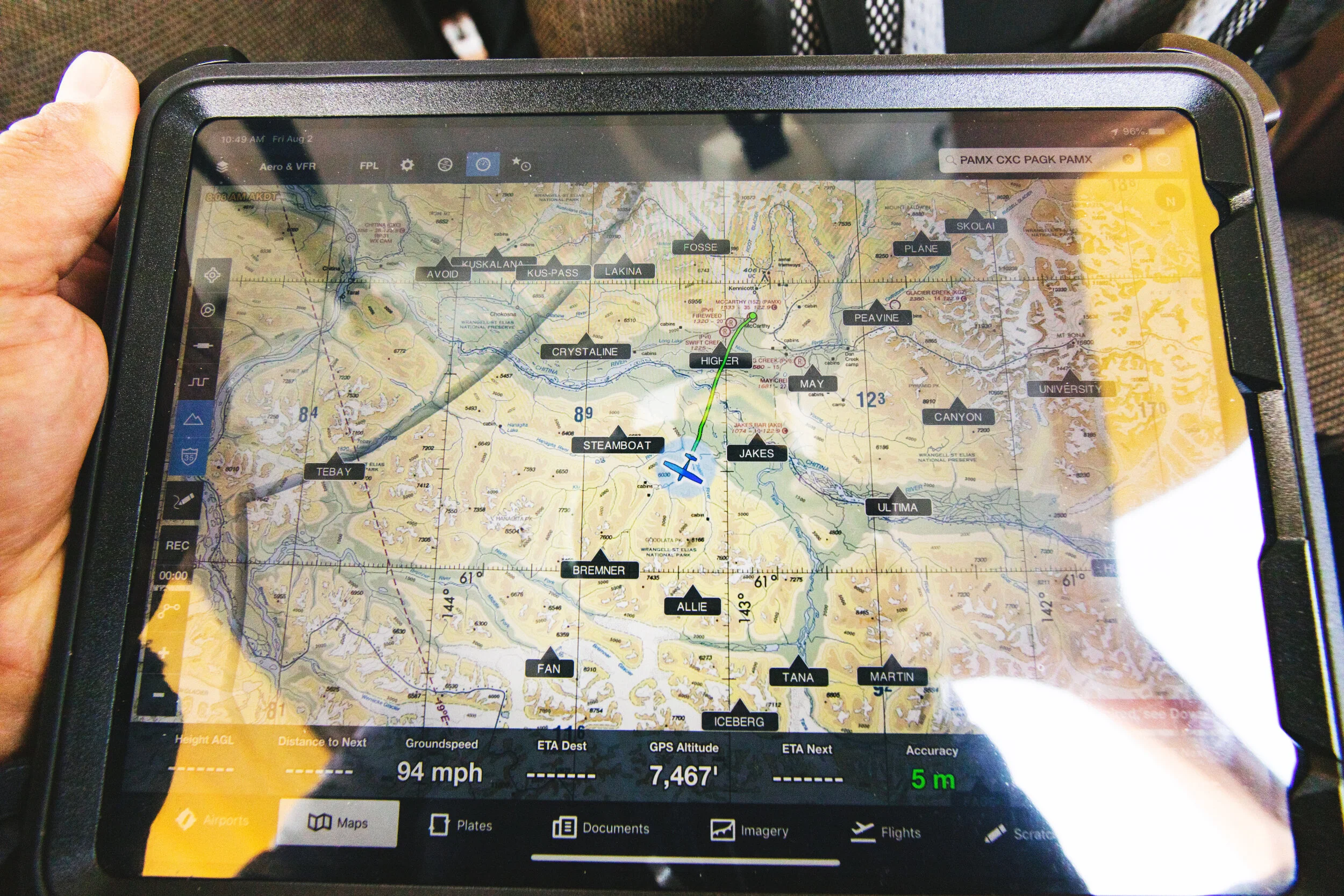

Ted orients us on our route for the day and alludes to just how uncharted this part of Alaska is. The navigational maps used by pilots here were last updated in the 1950s. Many glaciers have receded significantly in a matter of decades, rendering these maps inaccurate.

Our route today will take us south toward the Gulf of Alaska and over the Bagley Icefield. As I start to watch the infinite peaks scroll by beneath us, I'm beginning to feel lost, despite knowing exactly where I am.

It's hard to find the right language to describe this landscape. From the air, Wrangell-St. Elias National Park is a stunning visual treadmill of snow capped peaks, glaciers, and braided rivers. Take every geological feature you've seen in your life and compress it to be visible through two square feet of airplane window. Hit repeat.

The park is as vast as it is geologically diverse. It's the size of six Yellowstones. It holds 60% of Alaska's glacial ice. It contains nine of the 16 highest peaks in the United States. The knowns of this wilderness are only exceeded by its unknowns: most of the features we're seeing are unclimbed and unnamed.

FLAT, WHITE

As we venture south, Ted expertly describes the landscape, but I struggle to process it all. Gradually, the world below shifts unmistakably flat and white. We've reached the Bagley Icefield, which is the second largest subpolar icefield in North America. There's nothing like an expanse of ice 127 miles long, 6 miles wide, and 3,000 feet thick to help orient myself again.

ZOOMING IN

As the landscape becomes more familiar, I finally start noticing all of its peculiarities, many that I've never seen before in my life. Ted flies us over a rock glacier, which is composed of 90% rock, 10% ice. These formations are unique to Wrangell-St. Elias, Patagonia, and the Himalayas.

Ogives -- bands of alternating dark and light that form on glaciers below icefalls -- mark the yearly advance of some glaciers.

We spot troubling blooms of watermelon snow, perched above Jeffries Glacier -- a clear sign of climate change. Studies have shown that this reddish snow is 13% less reflective.

This park isn't just rock and ice. As we make our way back toward McCarthy, herds of Dall sheep dot the slopes.

Finally, the aftermath of a jökulhlaup (meaning "glacial run" in Icelandic), where rivers form seasonal lakes on top of glaciers. Every July, the glacial dam containing this lake breaks, draining millions of cubic feet of water downstream and leaving iceberg remnants on the lake floor.

TOUCHDOWN

It's regretfully time to return to McCarthy. Two hours have passed like 30 minutes. On the descent, we pass old copper mines, some forgotten, some restored. They represent the true pioneers who braved the innumerable peaks of this wilderness. If only they could have seen it like I have.

Ready to Fly Over Wrangell-St. Elias National Park?

With over 30 years of safe, unforgettable journeys, our experienced pilots are your trusted guides to America’s largest national park. Experience the unparalleled beauty of Wrangell St.-Elias National Park with Wrangell Mountain Air. From flightseeing tours to backcountry adventures, we’ll fly you to Alaska’s most remote and stunning destinations. We make wilderness accessible!

Book your flight today and let the adventure begin!